Feelin’ lucky? Try startup stock options. 🎰

It's like Vegas but with more spreadsheets and disappointment.

I’ve been gone for two years but the shenanigans have largely remained the same. Glory to Hanuman!

Let’s get into it.

Make ESOPs great again!

Here’s a rough idea of how startups work: a passionate founder has an idea that will change the world and create billions of dollars in value. But passion alone cannot make that dream a reality. Our founder must assemble a merry band of believers, a.k.a. employees, to execute this vision.

The job description is like a Horrible Bosses sequel: long hours, zero job security (this isn’t the civil service, ladies and gentlemen), and a market that could take one look at the product and say ‘Meh’. And the pay? Unremarkable.

Attracting and retaining your perfect merry band is tough.

But what if the founder had an ace up her sleeve? A way to convince risk-tolerant employees that their upside could extend far beyond their salaries?

Enter: Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), a way for employees to own shares in the companies they work for. On a long enough timeline, holding or selling those options could make them millionaires (the mechanics of an ESOP can be found here).

It’s classic delayed gratification: work at a startup where your job title might say “content lead,” even though you’re a one-person team (go ahead and add “Swiss Army Knife” to your LinkedIn bio), for the chance that one day, the company will be worth a gazillion dollars and your stake in it will fund your dream of making YouTube videos. Thank you Paystack, for making us believe.

Yet ESOPs can be a gamble because not every startup is Paystack, and sometimes, things get bizarre.

Take Vendease, a startup that helps restaurants buy food supplies. A recent TechCrunch article reported the startup laid off staff and slashed salaries:

“In the latest development, the startup [Vendease] has now replaced employees’ traditional salaries with a performance-based pay system, supplemented by an Equity Share Option Plan (ESOP), according to internal documents seen by TechCrunch.”

Then comes this next part, which manages to be worse:

“In February, all employees received a ₦140,000 (~$90) salary, regardless of previous pay. From March to May, the company will raise employees’ wages to 30% of former levels if they meet performance targets, though it hasn’t specified these targets.”

Vendease hopes an ESOP will soften the blow of a salary slash even though it only has operational cash to last a few months. It makes you wonder, who wants to gamble from what looks like a losing position? Also, if ESOPs are a bet on a company’s future, I cannot imagine a worse time to want to own Vendease stock options.

It must feel like a catch-22 for employees. I can imagine them updating LinkedIn with “open for work.”

Even in the best of times, stock options are rarely a compelling incentive to join Nigerian startups.

Many startups here are too young to unlock real value for employees, and accepting ESOPs instead of a proper living wage feels like a “heads you lose, tails you lose” situation.

In January 2025, employees at a B2B e-commerce company saw the value of their stock options evaporate after the cash-strapped company raised money with harsh liquidation preferences.

As always, my thoughts are with startup employees, who must feel like collateral damage in this race to find product-market Fit (PMF).

And speaking of startups making big promises only for reality to hand everyone a different hand, here’s another gamble: coding your way to wealth.

Coding your way to wealth meets cold, hard reality

It’s easy to talk about discipline and being conservative when there’s no money in the bank. The real test of willpower is when VCs are throwing money at you faster than you can say no and you feel sure the party will never end.

Spoiler: every startup eventually indulges in some questionable spending.

If you build a successful product, it’s all good and no one will care.

But if your company collapses, you become a headline, and people may or may not write threads and LinkedIn think-pieces about how you should have done things differently. Pay them no mind; it’s easy to talk when you don’t have millions sitting in the bank.

A Boom, A Frenzy, A Reckoning

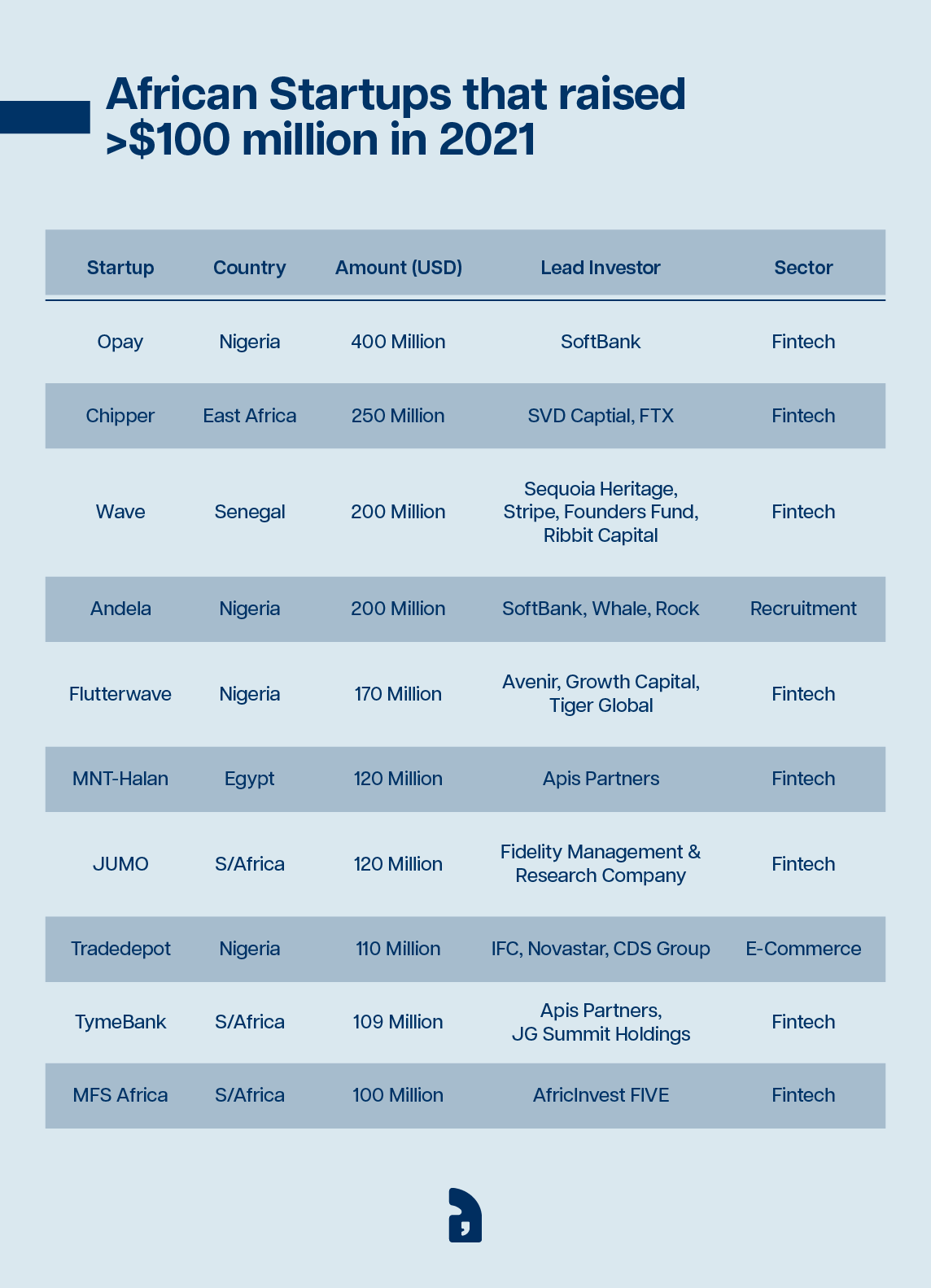

Come with me down memory lane to 2021, when a potent combination of zero interest rates in the U.S. (sending VCs farther afield than they would typically venture) and a pandemic-fueled online boom caused a flood of money to be pumped into African startups. Those were the days.

Startups raised so much money that some people argued the media should slow down on reporting fundraises (you miss those days, don’t you?).

Flush with cash, most Nigerian startups paid eye-popping salaries to attract talent from sectors like banking and FMCG, opened fancy new offices, and assumed that the good times would roll on forever. To be fair, this was a global phenomenon.

In all that exuberance, one class of talent became mini-gods: software engineers. With the pandemic making remote work popular, Nigerian software engineers got a taste of the global job market. Combined with the flood of VC money at home, they naturally began asking for more money. There was even a civil war over whether it was ethical for devs to hold two jobs.

In the middle of that gold rush, it became mind-numbingly easy to sell shovels. Coding schools, which had been around for a few years but hadn’t caught anyone’s attention, suddenly had a golden promise: learn how to code, and you could tap into these tech billions.

The early success of Lambda School (now Bloomtech), which trained developers for free and took payments only when students got jobs via income-sharing agreements, proved that this model could work. Andela also raised $40 million in a Series C round with a similar business model.Nigerian startups like Decagon and Semicolon also joined the fray.

Decagon’s founder and CEO, Chika Nwobi, admitted in 2018 that the startup was “probably the least innovative thing I have done.” Top marks for honesty and acknowledging that sometimes, originality is overrated.

In 2020, Decagon’s model looked like this: paying students a ₦40,000 monthly stipend, providing board and feeding, and training them for six months. Like Lambda, it allowed prospective software engineers to learn first and pay later, with students expected to pay back ₦3 million ($8,200) over a maximum of three years.

To sweeten the deal, learners who couldn’t afford the cost could take loans from Sterling Bank. To hear Decagon tell it, this was a foolproof investment.

They claimed a 100% success rate in getting full-time jobs for the first two cohorts. By 2022, they announced over 500 of their students had landed global roles and even secured a partnership with the Edo State government.

But things aren’t always what they seem.

Here’s a recent Techpoint article:

“Decagon, a Nigerian tech training institute, is shifting its focus away from tech education, according to sources familiar with the matter. The company, which previously specialised in software engineering training, will now concentrate on assisting learners in gaining admission to master’s programmes abroad.”

Remember that bit about originality? You can draw parallels between Decagon’s pivot and Lambda’s struggles.

Both startups used income-sharing agreements instead of upfront payments (Decagon later switched to a hybrid model). Both touted impressive placement results. And both eventually ran into the same problem: students weren’t repaying their loans.

Decagon’s Chika Nwobi once told TechCrunch that the startup had a 100% placement rate and a 100% loan repayment rate.

But Techpoint reports:

“Despite securing jobs after graduation, many graduates did not repay their loans, contrary to the 100% repayment rate Decagon had cited when it raised a seed round in 2021; some even refused to return the laptops provided by the institute.”

Lambda faced a similar reckoning:

“In early 2020, leaked communications with investors exposed dismal results. Most students weren’t hired. What little money the school made came from quietly reselling student debt to hedge funds. It turned out the income-share agreements were rigged. When graduates landed jobs unrelated to programming—everything from legal assistant to mailman—the company went after them anyway.”

The Elephant in the Room

For Decagon, this wasn’t just about the model. It was a hard market reality: there simply aren’t enough local companies to hire fresh software talent.

Andela figured this out early and focused on hiring senior developers and matching them with international gigs. Despite later shifting its focus to global roles, Decagon may have struggled to convince international companies to take a chance on entry-level talent with only one year of training.

Then there’s the big question: Was it merely difficult to get students to pay back their loans, or was this like Lambda, where the quality of jobs didn’t match income expectations? It’s hard to tell.

I can’t help but wonder if Nigerian banks will point to situations like this as examples of how difficult retail lending can be.

Also, how many neobanks that criticized traditional banks for not taking a chance on retail customers stepped up to finance these coding school loans?

What I’ve been reading:

This article on the problems at Lamda is from 2024 but it’s still worth a read

This hilarious article on what the U.S Congress is really like needs a Nigerian version ASAP

A tale about a succession battle for a prison empire. Needs a Netflix adaptation like yesterday

Also: Follow Notadeepdive on Twitter and Instagram. We’re cooking a few things there.

Final thoughts: I was sharing in a friend group yesterday that it felt like I’d been away from writing Notadeepdive for so long that I wondered if it would still be fun for everyone to read. One spoiler is that I enjoyed writing this and it felt pretty natural, so prepare to be sick of me.

Let me know in the comments if you enjoyed reading this.

See you on Sunday!

Happy to read from you again. I enjoyed this. Insightful as always.

Taking a deep dive into the fall of Lambda and the part where Austen started deleting students complaints is quite similar to an edutech academy here in the country.

And if they're not careful, in due season they might also hit rocks just like Lambda.